Editorials

We Study Climate Change, We Can’t Explain What We’re Seeing | The New York Times

by Gavin Schmidt and Zeke Hausfather | November 13, 2024

Excerpt:

The earth has been exceptionally warm of late, with every month from June 2023 until this past September breaking records. It has been considerably hotter even than climate scientists expected. Average temperatures during the past 12 months have also been above the goal set by the Paris climate agreement: to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius over preindustrial levels.

We know human activities are largely responsible for the long-term temperature increases, as well as sea level rise, increases in extreme rainfall and other consequences of a rapidly changing climate. Yet the unusual jump in global temperatures starting in mid-2023 appears to be higher than our models predicted (even as they generally remain within the expected range).

Looking Back: John Chiara | Photograph Mag

March 1, 2024

Excerpt:

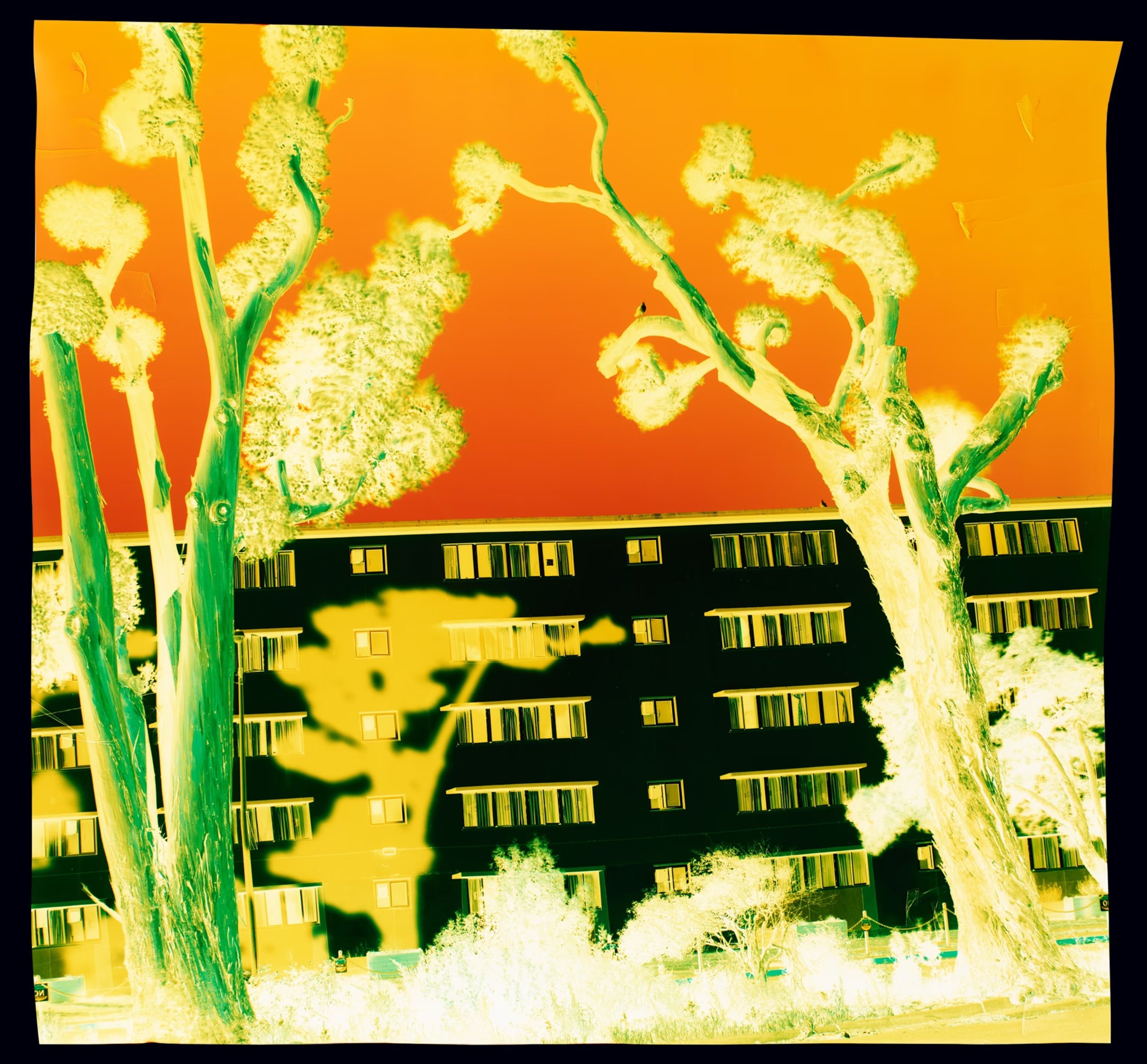

In late February, 2020, I made my way to the Fundaziun Nairs residency program in the southeastern Swiss Alps. While I was speeding on the Austrian Autobahn in my Ford Ranger rental with Hungarian license plates, my left back wheel came off. I watched it fly past me on the highway and blast over a fence. It was a harbinger of a time when history would go off the rails.

Shortly after I arrived at the residency, the Swiss borders closed due to the coronavirus. The town shut down, and most people fled. The solitude there, and working with the landscape, seemed to counter the turbulence of the global pandemic. I wanted to figure out how to capture the feeling of watching the energy that flows through the Alps.

Let’s not waste this crucial moment: We need to stop abusing the planet | National Geographic

by Robert Kunzig | Oct 13, 2020

Can Genetic Engineering Bring Back the American Chestnut? | The New York Times

by Gabriel Popkin | April 30, 2020

Excerpt:

Sometime in 1989, Herbert Darling got a call: A hunter told him he had come across a tall, straight American chestnut tree on Darling’s property in Western New York’s Zoar Valley. Darling knew that chestnuts were once among the area’s most important trees. He also knew that a deadly fungus had all but wiped out the species more than a half-century earlier. When he heard the hunter’s report of having seen a living chestnut whose trunk was two feet thick and rose to the height of a five-story building, he was skeptical. “I wasn’t sure I believed he knew what one was,” Darling says.

The Past and the Future of the World’s Oldest Trees | The New Yorker

by Alex Ross | January 13, 2020

Excerpt:

About forty-five hundred years ago, not long after the completion of the Great Pyramid at Giza, a seed of Pinus longaeva, the Great Basin bristlecone pine, landed on a steep slope in what are now known as the White Mountains, in eastern California. The seed may have travelled there on a gust of wind, its flight aided by a winglike attachment to the nut. Or it could have been planted by a bird known as the Clark’s nutcracker, which likes to hide pine seeds in caches; nutcrackers have phenomenal spatial memory and can recall thousands of such caches. This seed, however, lay undisturbed. On a moist day in fall, or in the wake of melting snows in spring, a seedling appeared above ground—a stubby one-inch stem with a tuft of bright-green shoots.

[Download]

John Chiara’s Uncanny City | The New York Times

by Luc Sante | July 11, 2018

Excerpt:

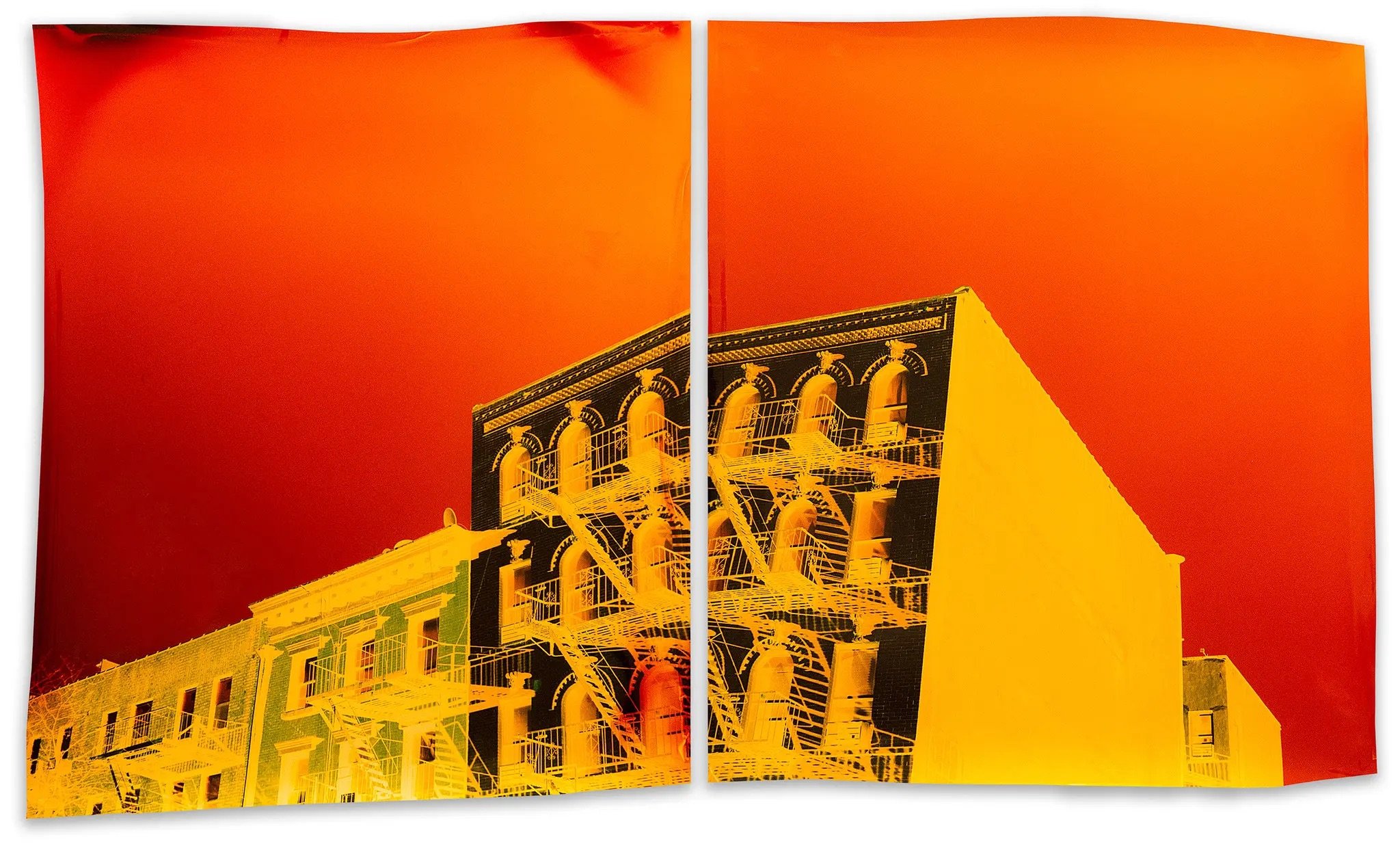

The titanic architecture of what may be the world’s second-most-photographed city (if Paris still holds the top spot) has been shot again and again, with steadily diminishing returns. It will never again be possible to match the awe that attended the sight of the Flatiron Building upon its construction in 1902, as shown in the many pictures taken of it then by Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Alvin Langdon Coburn and dozens of others. Nor will anyone ever again capture the time when high-rises first began to multiply, as Berenice Abbott did in the 1930s, shooting the resultant canyons, the competing spires, the first night scenes from above. It has become ever more difficult to evoke the shock of the new, especially now that there are so many skyscrapers that nothing short of a hundred stories can command much attention. These days they can just look like walls or hedges, and the skyline looks like a toothbrush.

John Chiara – Pike Slip to Sugar Hill | The Eye of Photography

September 6, 2018

For his second solo exhibition at the gallery, John Chiara handcrafted a custom 50″ x 40″ camera designed to capture Manhattan’s soaring verticality in kaleidoscopic color and with hyperreal clarity. Driving the enormous camera around the city in the bed of a commercial pickup truck, Chiara photographs NYC’s streets and its architecture with equal admiration for glass office towers, Beaux-Arts facades and the backsides of 19th century tenements.

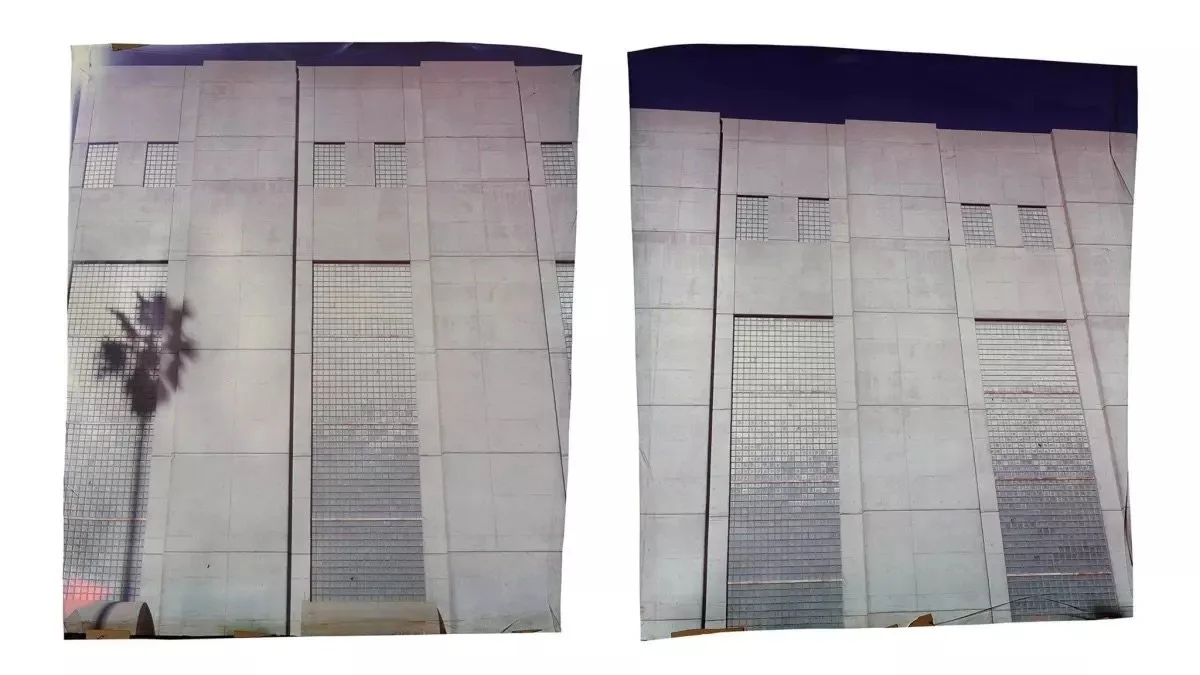

Through the precision barrel lens, images are projected directly onto the scroll of color photographic paper inserted into the camera. During exposure, Chiara burns, dodges and filters the light entering through the lens, working to change the temperature of light and spectrum of color as if in the darkroom. As the image is received onto negative paper, light and shadow are reversed, as are the colors, casting his anonymous skyward views in otherworldly hues. At times resembling a blueprint, an image captured through night vision goggles or an x-ray, the unexpected palette jolts the eye from its malaise of familiarity to a heightened awareness of detail and the rich collage of textures that is New York City.

California Today: An Analog View of California | The New York Times

by Mike McPhate | October 27, 2017

Excerpt:

John Chiara does his photography from scratch.

Even as taking pictures has gotten simpler, Mr. Chiara, 46, constructs his own box cameras — known as camera obscuras — that draw in light through a small hole onto photographic paper.

His biggest camera is the size of a small elephant, which he hauls on a trailer and positions in front of his subjects.

To take a photograph, he squeezes his body inside the camera and pulls a trap door behind him. He positions a sheet of photographic paper as large as four feet by six feet and then manipulates the light and length of exposure.

A single picture takes about half a day.

The approach invites anomalies — light leaks, flares, hallucinatory colors — that might make some photographers recoil.

Big Town, Big Camera | The New York Times

by John Leland | April 15, 2016

Excerpt:

At a time when taking photographs has never been easier, John Chiara shot New York City the hard way. Mr. Chiara, 44, who lives in San Francisco, built two box cameras the size of kitchen cabinets and loaded them with large sheets of photosensitive paper that produced negatives of the colors projected on it. “New York is a very challenging place to photograph, because it’s been photographed so much,” he said. “It was exciting figuring out what I had to bring to it.” The results are an alternate city that evokes the chaos and monumental architecture of the real thing but invites people to meditate on it rather than rush through. “I wanted it to feel like a fragment of a memory,” he said. “It’s like the visual you get when you’re staring into space, trying to reconcile what you remember with what you saw. You don’t get the whole thing at once. You have moments of clarity, but it’s elusive.” The cameras each took weeks to build; the shooting took the better part of a year. With any image, he never knew quite what he had until he saw the finished print.

In Camera: John Chiara's American Landscapes | British Journal of Photography

by Tom Seymour | April 6, 2016

Excerpt:

Chiara’s unique process, which is to be exhibited by Next Level gallery in Paris, produces one-of-a-kind large-scale prints. His approach consciously recalls the early days of the medium when artists dealt with heavy, awkward equipment and endured long exposure and development times.

The design of the cameras, which is much like daguerreotype box cameras, allows the artist to simultaneously shoot and perform his darkroom work while images are recorded directly onto oversized photosensitive paper.

John Chiara, and California’s Beauty and Terror | Guernica Mag

by Sophie Haigney | April 18, 2018

Excerpt:

When I saw John Chiara’s photographs of California for the first time, I thought of wildfires. It was still fire season in late December of 2017, and smoke from Montecito was blowing up to San Francisco. Each day I counted as the acres of flame grew and grew. I spent much of my time looking at footage of the fires. I’d seen the Getty Museum surrounded on all sides by flames on CNN.

Nothing Outdated About John Chiara’s Traditional Techniques | KQED

by Matthew Harrison Tedford | November 15, 2017

Excerpt:

We’re accustomed to the idea that photographs — unlike paintings — can be infinitely reproduced. However, the earliest photographs were one-of-a-kind images exposed directly onto a light-sensitive plate. Even though reproducible techniques were introduced early in the history of photography, unique photographs, such as daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes, remained popular for decades, before ultimately losing ground. There’s still something attractive in the unique image. Less popular than it once was, instant film was a modern fulfillment of this same desire.

Chiara’s latest solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Haines Gallery, Lands End: California at Larkin, showcases 16 of his newest works. Though Chiara also has a new book, John Chiara: California, that features work taken throughout the state, Lands End focuses solely on works photographed between Pescadero and the Marin Headlands.

In Camera: John Chiara's American Landscapes | The British Journal of Photography

by Tom Seymour | April 6, 2016

Excerpt:

Chiara’s unique process, which is to be exhibited by Next Level gallery in Paris, produces one-of-a-kind large-scale prints. His approach consciously recalls the early days of the medium when artists dealt with heavy, awkward equipment and endured long exposure and development times.

The design of the cameras, which is much like daguerreotype box cameras, allows the artist to simultaneously shoot and perform his darkroom work while images are recorded directly onto oversized photosensitive paper.

[Download Article]

Photographing California with a camera as big as a truck | LA Times

by Agatha French | October 26. 2017

Excerpt:

Striation across a burst of bougainvillea draws attention to itself, reminding the viewer of the work and chemistry that went into creating it. The edges of the photographs are slightly wavy and uneven, an indication that the photographic paper is a physical thing that can twist and buckle. Among the pleasures of these photographs are their nuance and individuality. Unlike a film negative or a digital image that can be printed in many multiples, his photographs exist only in their original form (and the images that are taken of them, like this book).

Chiara’s process takes time, from scouting to developing. “I have to go and really spend time someplace before the work starts really happening,” he said. “It’s a matter for going out and really looking.” In conversation, he refers to the experience of shooting as an “event.”

John Chiara’s Sidewalk Studio: A Conversation with Allie Haeusslein | Aperture

June 8, 2016

Excerpt:

Allie Haeusslein: Could you describe your process?

John Chiara: I build out the equipment and processes to physically produce the work given those parameters. The equipment and process both revolve around the type of lens and positive, color photographic paper I use. When I’m out shooting, I directly expose the paper, dodge, burn, and filter the light as if I were working in the darkroom. I have been working with this intuitive process for about twenty years now. Often, I work from the inside of a large camera obscura to expose photographic paper up to 50-by-80 inches. I then develop the image using a section of capped PVC pipe filled with chemistry and then roll the tube across the studio floor to process the photograph.

[Download]

John Chiara's camera obscura captures big picture | SFGATE

by Sam Whiting | June 16, 2011

Excerpt:

When John Chiara photographs the Golden Gate Bridge, he hauls his gear out to the Marin Headlands, sets up facing east, then climbs inside the camera and pulls the trapdoor closed behind him.

An hour later, he climbs back out with an image vast and deep enough to capture both bridges plus the skyline and the hills, set against a foreground of shimmering bay water. The picture cannot be reproduced, and neither can the camera, which fits in a black wood and foam box 8 feet wide and 5 feet tall. A lens the size of a magnum Champagne bottle is at the front, and a giant sheet of color photography paper is at the back, with room between for Chiara, who is 6 feet 2 and 220 pounds, to squeeze himself in like the Great Houdini.